Batik and ukiyo-e woodblock printing share more than just dazzling outward beauty; both design forms are firmly founded on a rich cultural heritage—one from the tropical islands of Indonesia, the other from the artful streets of Edo-period Japan. And, as cultures evolve and the world becomes more interconnected, these two customary crafts are finding new and exciting expressions. Batik and ukiyo-e represent deep-rooted cultural identities and unique stories, and their fresh forms highlight a global curiosity about shared creativity.

Batik: Indonesia’s ink-and-wax canvas

Batik dates back to ancient Indonesia, as early as the 4th century CE, approximately 1,625 years ago. The technique of decorating fabric using hot wax and dye became highly developed in the 13th century, evolving a highly regarded artform. The process is intricate: areas of the cloth are covered in wax to resist the dye, while the rest is soaked in vibrant colors. This creates stunning patterns, often full of symbols representing nature, the cosmos, or cultural traditions. Batik is so significant in Indonesia that in 2009, UNESCO recognized it as an Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Java, particularly, is the center for batik making, where traditional methods meld with customary and modern designs, alike. Laweyan Batik Village—a famed historical site and the oldest batik industry center in Surakarta, Java—has been recognized as a national cultural heritage site, for its conservation of batik-making culture and its centuries-old architecture.

What sets batik apart is its versatility—whether it’s used in clothing, home décor, or even ceremonial pieces, batik is a canvas for artful Indonesian expression. Batik makers like Batik Danar Hadi, Batik Keris, and Bateeq continue to push the artform forward, creating both traditional designs and contemporary interpretations that appeal to local and international tastes, alike.

Ukiyo-e: Japan’s block print legacy

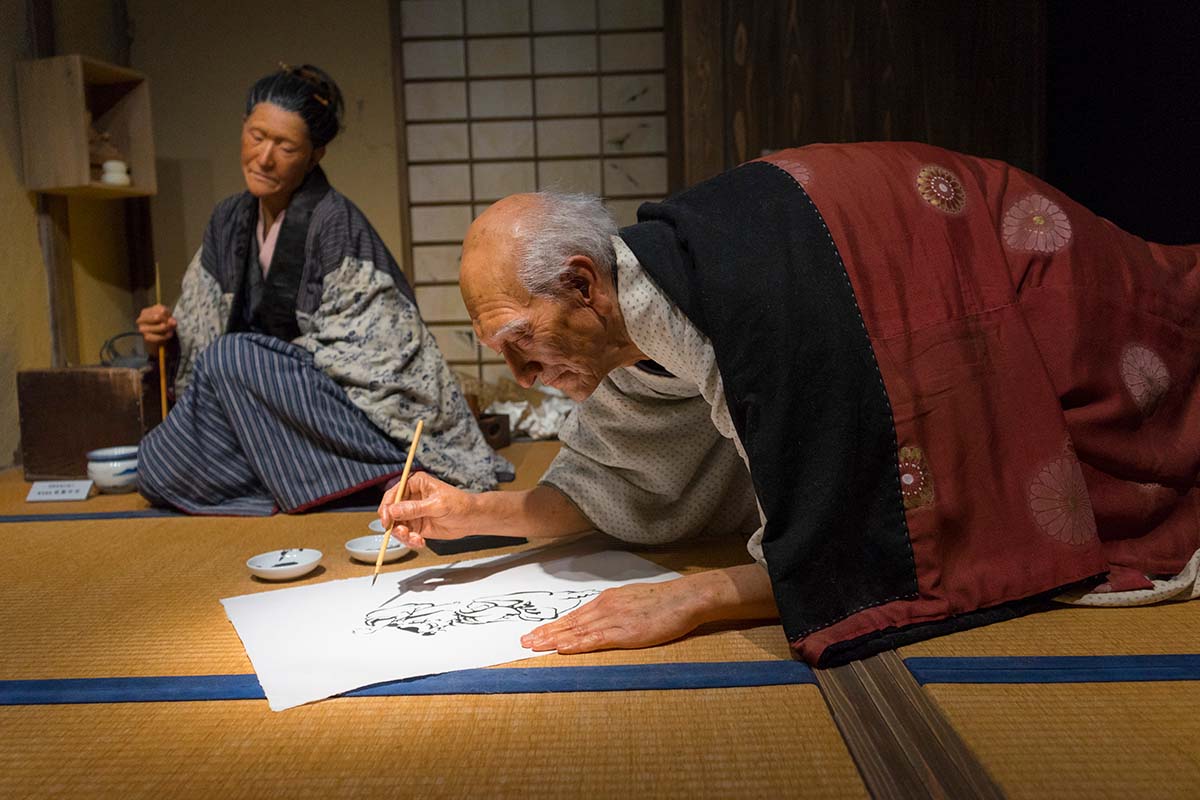

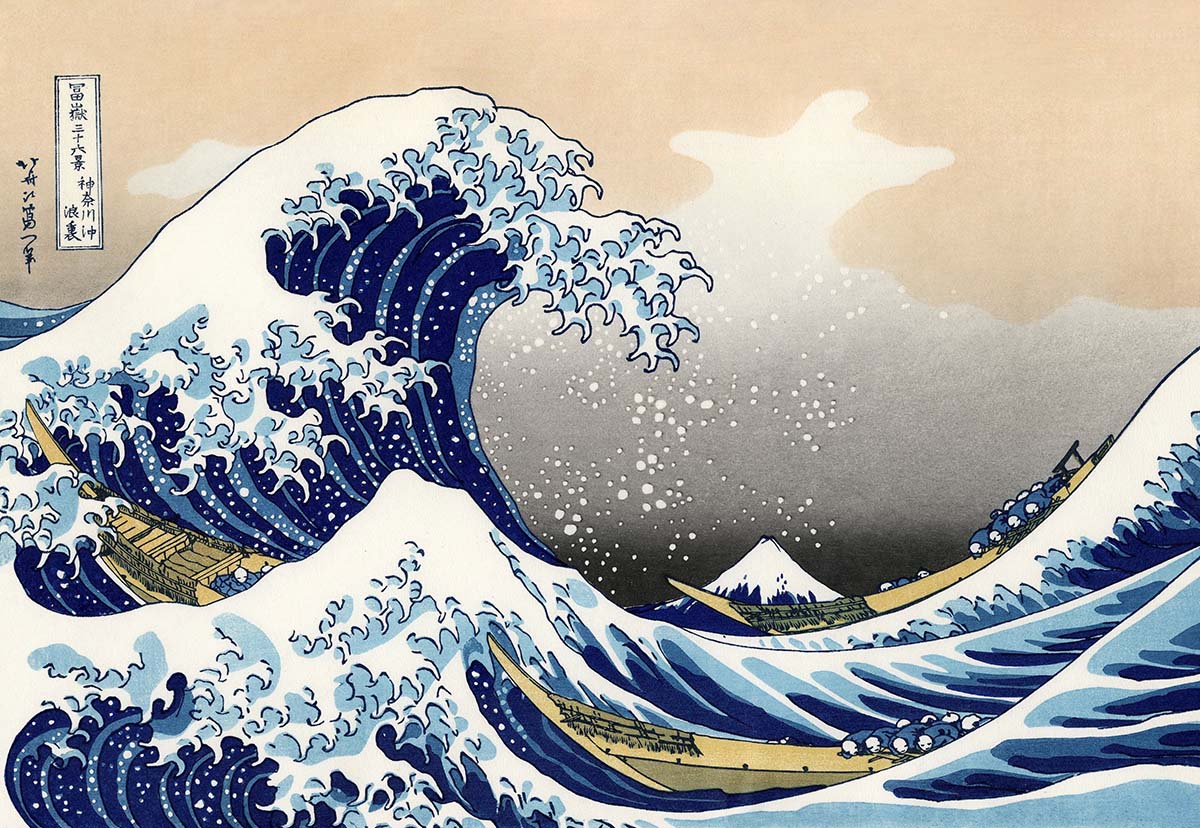

In contrast, ukiyo-e, the Japanese woodblock printing tradition, emerged during the Edo period (1603-1868). Ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the floating world,” captured scenes from daily life, such as landscapes, kabuki actors, and beautiful women. The prints were mass-produced, allowing these artworks to reach a broader audience. Masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige revolutionized ukiyo-e—adding natural elements, landscapes, and scenes from daily life—making it one of the most influential art movements in Japan and inspiring artists worldwide.

Ukiyo-e stands out for its distinct layering technique. Artists carve intricate designs into wooden blocks, apply ink, and press them onto paper, creating richly colored prints. Ukiyo-e artists often used symbolic imagery, combining both realism and abstraction. Today, ukiyo-e can be found in modern adaptations, with contemporary artists reinterpreting traditional themes in new media.

Crossovers between Batik and Ukiyo-e

Although batik and ukiyo-e evolved in different parts of the world, their shared emphasis on repetition of motifs and symbolism makes them strikingly similar in purpose. While batik focuses on color and fabric, ukiyo-e celebrates color and form on paper. Both are historically tied to culture and social context, presenting scenes of life, nature, and identity.

Batik and ukiyo-e aren’t just ancient traditions—they’re still alive and kicking today, influencing modern design in unique ways.

Batik and ukiyo-e aren’t just ancient traditions—they’re still alive and kicking today, influencing modern design in unique ways. Batik, for example, is a staple in contemporary Indonesian fashion. It’s more than just a beautiful pattern—it’s a technique that’s been practiced for centuries! Fun fact: the word batik comes from the Javanese word ambatik, meaning “a cloth with little dots,” which refers to the wax-resist dyeing process that creates its signature look. Even today, the art form is featured in everything from traditional sarongs to modern dresses.

Meanwhile, ukiyo-e continues to inspire the art world in Japan. The woodblock prints, originally created during the Edo period (1603-1868), are still a massive influence on contemporary Japanese art. One of the most famous ukiyo-e artists, Katsushika Hokusai, created The Great Wave off Kanagawa—a print so iconic it’s recognized worldwide. While you won’t see batik and ukiyo-e mashed together in the latest fashion line (yet! It’s only a matter of time before someone thinks of it, really), both traditions still show up in unexpected ways, like in art exhibitions, pop culture, and even tattoos. Fun fact: Many modern Japanese graphic designers openly credit ukiyo-e for inspiring their style—especially the use of dramatic lines and flat, bold colors. Ukiyo-e also influenced Western artists like Van Gogh, who was known to collect Japanese woodblock prints, which had significant impact on his art and paved the way to the Japonisme movement.

Ancient art forms, fresh vibe

The world of batik and ukiyo-e isn’t just about nostalgia and time-honored tradition—it’s about reinvention. In Indonesia, batik’s intricate patterns are being reimagined on runways and in the heart of contemporary interiors, telling stories that blend the old with the new. Meanwhile, Japan’s ukiyo-e continues to shape everything from the captivating chaos of street art to the sleek stylings of anime, proving that the past is far from outdated. These timeless art forms are alive and evolving, pushing boundaries while staying true to their roots. Their journey is only just beginning, and the future looks as colorful and dynamic as the art itself.